Milk production per cow has dramatically improved in the last 50 years. This productivity has led to fewer cows on fewer farms producing a larger volume of milk each year.

Certainly, there are many things that impact milk production, including genetics, housing, nutrition and so forth, but cow health and risk of disease are also of great importance. We know there are several chronic diseases that can lower production. Some of these diseases are readily apparent, like mastitis or lameness. However, others can be more silent within a herd and often go undetected for long periods of time.

BLV is a big one

Bovine leukosis virus (BLV) commonly infects cattle and has a widespread distribution throughout North America. Once cattle are infected, they remain carriers of the disease for life and can infect other animals.

We used to think that other than causing cancer, the virus was fairly benign in cattle and really didn't cause any other significant problems. However, more recent research suggests that subclinical infection can cause other economic losses in a dairy herd.

One of the difficult things about BLV control is that the vast majority of infected cattle will never show clinical signs of disease. Less than 5 percent of cattle infected with BLV ever actually develop cancer. So, dairy producers often don't consider it economical to spend a lot of time and money controlling this disease.

Several recent studies have shown that BLV reduces milk production and shortens longevity of cows within a herd. Data from the National Animal Health Monitoring Survey (NAHMS) 1996 dairy study indicated that herds with BLV-positive cows produced 480 pounds less milk than herds that were largely BLV-negative. Mean annual production value per herd dropped by $1.28 for every 1 percent rise in herd BLV prevalence in this study.

A more recent study done in Michigan looked at production records from 104 dairy farms (about 40 cows per dairy) and compared milk production to BLV status. This study also showed that the presence of BLV was negatively associated with herd milk production. Losing a cow every now and then to cancer is no longer the only negative consequence to having BLV in your herd.

Johne's cows milk less

Johne's disease (JD) is a chronic disease of ruminants caused by infection with the bacteria Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP). While it is obvious that animals showing clinical signs of Johne's become less productive, there has been a significant amount of research investigating the milk loss associated with subclinical infection earlier in the course of disease. Although results have been inconsistent, the vast majority of studies completed to date show some degree of lost milk associated with Johne's disease ranging from 2 to 25 percent.

In the 2002 NAHMS dairy study, more than 5,700 cows from 38 dairy farms in 16 states were tested using the Johne's ELISA. Cows that were positive for MAP had milk production totals in their current lactation of 880 pounds less than negative cows, and those that tested strong positive had milk productions of 3,000 pounds less than negative cows. Positive cows also had very significant drops in lifetime milk production.

Another large study looked at serum ELISA and fecal culture results for MAP from 4,375 Holstein cows from 232 herds in their first three lactations. The results of this study showed that Johne's-positive cows produced 670 pounds less milk per lactation as compared to negative cows. This study also found that cows that actually cultured positive for MAP had greater production losses as compared to cows that tested positive for Johne's disease by ELISA but were culture negative.

Additional studies from Canada, France, Germany, Iran and the United States have all found significant production loss associated with subclinical Johne's infection. Therefore, working to reduce the within-herd prevalence should be a priority for producers. The decision to cull positive cattle should be relatively easy for producers looking to control Johne's disease on their farms.

Neosporosis affects more than repro

Neospora caninum is a protozoan parasite recognized as an important pathogen associated with abortion in cows. Although Neosporosis is primarily related to reproductive losses in cattle, several studies have shown that it can also cause lost milk production.

For example, a study in California followed the first lactation of 372 Holstein cows. Weekly milk tests showed that the production from the 118 positive cows was 2.7 pounds per cow per day less than the 254 negative cows. Another study looked at 565 Holstein cows of varying age and lactation number on a dairy in Florida. Cows that were positive for Neospora produced 3 pounds per cow per day less milk when compared to negative herdmates.

A large study across 83 dairy herds in Ontario followed 3,702 cows during a lactation and divided them into groups depending on whether or not they were positive for Neosporosis. The positive cows made 607 pounds less in 305-day milk production.

Although the exact mechanism or cause of lost production due to Neospora is not well understood, data from multiple studies would indicate that this is certainly a disease that can cause mild to moderate decreases in milk.

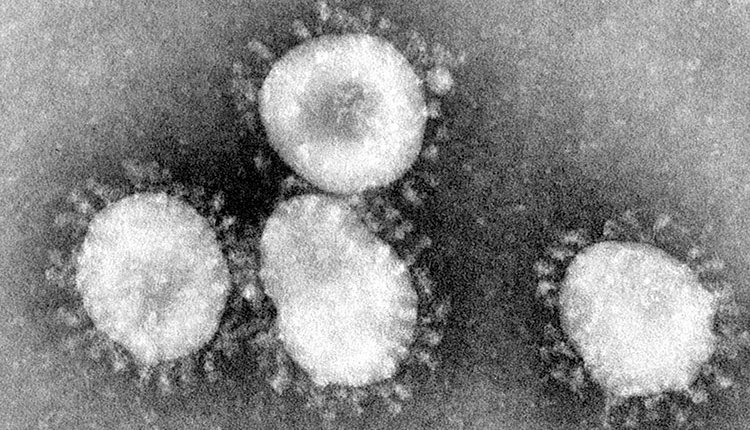

Subclinical BVD takes milk, too

BVD is a worldwide cattle pathogen with moderate to high prevalence in many countries. Infection may be subclinical in many cases with the primary economic losses coming from abortions, infertility and calves born with congenital defects. Dramatic drops in milk production have been associated with herds experiencing outbreaks; however, subclinical BVD infection may lower milk yield, as well.

For example, a study in Sweden where BVD vaccination is not routinely done identified 319 "infected" herds and compared them to 2,270 control or "uninfected" herds. This study showed a significant decline in milk production associated with BVD infection ranging from 312 pounds per lactation in smaller herds to 560 pounds in larger herds.

In a Canadian study, 90 dairy herds were evaluated. Cows in positive herds (defined as having unvaccinated animals with titers greater than 1:64) had an 810-pound per-cow per-lactation drop in milk production as compared to negative herds. Although the economic effects of BVD on milk yield in North America are very hard to quantify as most herds vaccinate, BVD can affect milk yield and should remain near the top of the list of concerns for dairy producers.

Obviously, there are other diseases that can negatively impact performance. However, BLV, Johne's, Neospora and BVD represent the major chronic diseases of cattle in North America that producers and veterinarians should be aware of and work to aggressively control in high-producing dairy herds.