The author is a research aide in the College of Veterinary Medicine at Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.

As every dairy producer knows, clinical mastitis is a common and persistent problem. It may occur several times during a lactation, with various consequences on milk yield, reproduction, cow well-being, death, sale, and, ultimately, on the profitability of your enterprise. We wondered if subsequent cases had different effects than the first case. Given the question's importance, we received USDA funding to investigate the impact of multiple cases of mastitis on the production and economics of the cow.

In this article, focus on "pathogen-unidentified" mastitis; that is, you observe only clinical signs of it. We discuss the effects that we have seen regarding recurrent cases on milk yield, conception, death, and sale in New York Holsteins.

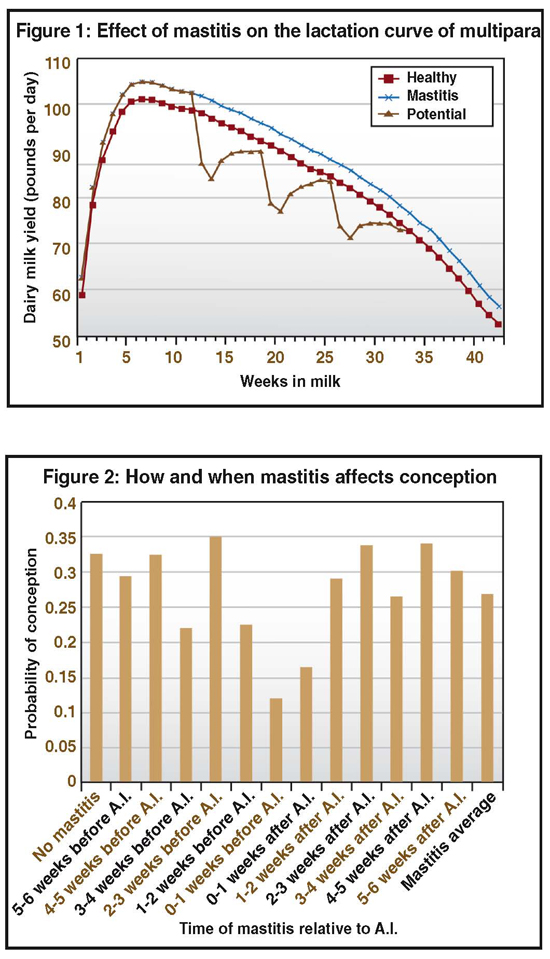

Future articles will explore the consequences if further information is known, such as whether the bacteria is gram-positive or gram-negative, or what the actual pathogen(s) is.

Effects on milk yield . . .

We studied 10,380 lactations in five large, high-producing New York herds with low overall incidences of contagious mastitis pathogens. Twelve percent of first-calf heifers had at least one mastitis case, 2 percent had a second case, and 1 percent had a third. In older cows, these incidences were higher: 24, 8, and 3 percent, respectively.

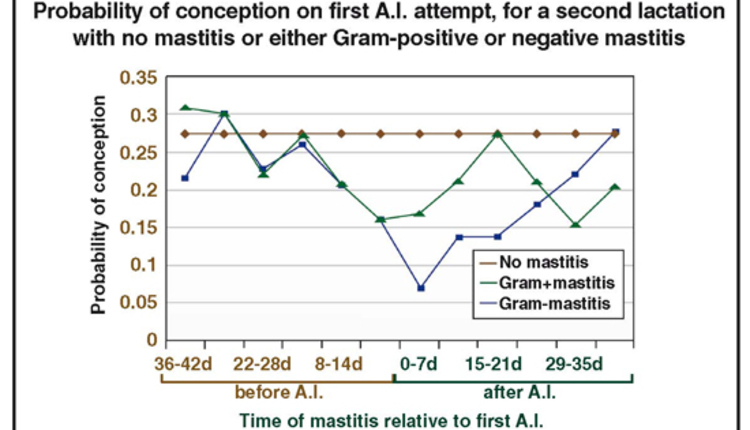

Figure 1 shows three lactation curves. The "healthy" curve is of a cow without mastitis. The "mastitis" curve shows the milk yield of a cow that had three cases of mastitis. The "potential" curve shows the milk yield that the mastitic cow would have had if she had remained mastitis-free.

We can see that there is a substantial drop in milk yield after each case, and it takes some time to recover. In fact, we can see that a mastitic cow never regains her potential yield. The same was true of first-calf heifers as well as cows.

Getting to the precise estimates, in first-lactation cows, we found significant losses in the eight-week period after diagnosis of the first case. This ranged from 2.4 to 8.4 pounds per day. The greatest losses occurred immediately after diagnosis, and then they gradually declined. In the eight weeks after diagnosis, the total loss associated with a first case was 361 pounds.

Even greater losses were associated with the second case: 12.8 pounds per day in the first week after diagnosis and 9.9 pounds per day in the second week. Then there was a gradual decline, for an eight-week loss of 436 pounds. The only significant loss (6.4 pounds per day) associated with a third case was in the first week after diagnosis. Interestingly, mastitic cows outproduced their nonmastitic herdmates by 1.5 pounds per day before mastitis occurred.

In second-lactation and older cows, losses were higher, but, of course, they are higher yielders than first-calf heifers. These cows lost 10.8 pounds per day in the week after diagnosis of the first case and 13 pounds per day in the following week. Thereafter, losses gradually declined but were still 1.5 pounds per day seven weeks later.

The total loss associated with a first case, during the eight weeks after diagnosis, was 557 pounds with the older cows. With the second case, again the greatest losses were in the first two weeks after diagnosis: 12.3 and 13 pounds per day, respectively. Five weeks later, mastitic cows had recovered their production. The total eight-week loss associated with a second case was 524 pounds. A third mastitis case was a bit less detrimental, but losses in the first two weeks still were more than 9 pounds per day.

After five weeks, mastitic cows were producing the same amount as nonmastitic cows but still below their potential. The eight-week loss associated with a third case was 475 pounds. Additionally, we found that even one mastitis case in a lactation was associated with an 880- pound drop in production in the next lactation.

Better cows; more mastitis . . .

So, what have we learned about recurrent mastitis cases and milk production? First, mastitic cows tend to be higher producers than nonmastitic cows before they experience mastitis. Therefore, we should pay particular attention to the higher producers in our herds that are exhibiting clinical signs of mastitis. Focusing on this group of cows, especially if resources (labor, and so forth) are scarce, could save your enterprise a substantial amount of money by catching mastitis cases early and treating them promptly before they cause too much damage or before they even need (antibiotic) treatment. These measures would reduce both absolute milk loss and milk produced but needing to be discarded due to antibiotic presence.

Second, first-calf heifers lost more milk after a second case (436 pounds) than after a first case (361 pounds). The opposite was true for older cows where milk loss was less severe for subsequent cases (557, 524, and 475 pounds for the first, second, and third case, respectively).

Our findings provide information on the differing milk losses associated with mastitis cases, without needing to know the causative agent. Armed with such knowledge, you can better assess the profitability of individual cows. Cows that have repeat mastitis cases may be less desirable to hold on to, as they experience large production drops with every case, taking weeks to recover . . . never returning to their high potential.

As observed by many dairy producers, we have found that mastitic cows have lower conception rates after artificial insemination (A.I.) and delayed days to first breeding. More recently, we also have found that the timing of mastitis with respect to A.I. can affect the probability of conception.

If mastitis occurred one or two weeks before A.I., probability of conception dropped by 44 percent. If it occurred in the week before A.I., the drop was much greater at 73 percent. If it occurred during the week after an A.I., the decline was 52 percent. So, obviously, mastitis has an impact on reproduction, and it varies with when it occurs (Figure 2). It actually may make sense to refrain from breeding a mastitic cow, and wait for the next cycle, by which time she, hopefully, may have recovered. These are important things to consider when estimating the total cost of a mastitis case.

Shortens life . . .

We also calculated the probabilities of death and sale for a combination of factors (parity, timing of mastitis, stage of lactation, and so forth), based on 16,145 lactations in five New York herds. We found that those probabilities vary with case number and the timing of each case. Mastitis clearly has a detrimental effect on a cow's herd life . . . the probabilities of dying or being sold are much higher for mastitic cows than for nonmastitic cows.

For example, in a second-lactation cow, sale is much more likely after a second case only if it occurs in the first 60 days in milk (approximately 0.05). After this time, it hardly seems to matter if the cow had a second case (0.013 versus 0.011 for a nonmastitic cow). Such results also can be used to economically assess different mastitis management options.

In this article, we have discussed the consequences of mastitis if you only know that your cow had mastitis based on clinical signs. As we have seen, recurrent mastitis cases have different consequences relating to milk yield, conception, death, and sale. We hope that this article has provided some useful information on the varying consequences of mastitis cases.

As every dairy producer knows, clinical mastitis is a common and persistent problem. It may occur several times during a lactation, with various consequences on milk yield, reproduction, cow well-being, death, sale, and, ultimately, on the profitability of your enterprise. We wondered if subsequent cases had different effects than the first case. Given the question's importance, we received USDA funding to investigate the impact of multiple cases of mastitis on the production and economics of the cow.

In this article, focus on "pathogen-unidentified" mastitis; that is, you observe only clinical signs of it. We discuss the effects that we have seen regarding recurrent cases on milk yield, conception, death, and sale in New York Holsteins.

Future articles will explore the consequences if further information is known, such as whether the bacteria is gram-positive or gram-negative, or what the actual pathogen(s) is.

Effects on milk yield . . .

We studied 10,380 lactations in five large, high-producing New York herds with low overall incidences of contagious mastitis pathogens. Twelve percent of first-calf heifers had at least one mastitis case, 2 percent had a second case, and 1 percent had a third. In older cows, these incidences were higher: 24, 8, and 3 percent, respectively.

Figure 1 shows three lactation curves. The "healthy" curve is of a cow without mastitis. The "mastitis" curve shows the milk yield of a cow that had three cases of mastitis. The "potential" curve shows the milk yield that the mastitic cow would have had if she had remained mastitis-free.

We can see that there is a substantial drop in milk yield after each case, and it takes some time to recover. In fact, we can see that a mastitic cow never regains her potential yield. The same was true of first-calf heifers as well as cows.

Getting to the precise estimates, in first-lactation cows, we found significant losses in the eight-week period after diagnosis of the first case. This ranged from 2.4 to 8.4 pounds per day. The greatest losses occurred immediately after diagnosis, and then they gradually declined. In the eight weeks after diagnosis, the total loss associated with a first case was 361 pounds.

Even greater losses were associated with the second case: 12.8 pounds per day in the first week after diagnosis and 9.9 pounds per day in the second week. Then there was a gradual decline, for an eight-week loss of 436 pounds. The only significant loss (6.4 pounds per day) associated with a third case was in the first week after diagnosis. Interestingly, mastitic cows outproduced their nonmastitic herdmates by 1.5 pounds per day before mastitis occurred.

In second-lactation and older cows, losses were higher, but, of course, they are higher yielders than first-calf heifers. These cows lost 10.8 pounds per day in the week after diagnosis of the first case and 13 pounds per day in the following week. Thereafter, losses gradually declined but were still 1.5 pounds per day seven weeks later.

The total loss associated with a first case, during the eight weeks after diagnosis, was 557 pounds with the older cows. With the second case, again the greatest losses were in the first two weeks after diagnosis: 12.3 and 13 pounds per day, respectively. Five weeks later, mastitic cows had recovered their production. The total eight-week loss associated with a second case was 524 pounds. A third mastitis case was a bit less detrimental, but losses in the first two weeks still were more than 9 pounds per day.

After five weeks, mastitic cows were producing the same amount as nonmastitic cows but still below their potential. The eight-week loss associated with a third case was 475 pounds. Additionally, we found that even one mastitis case in a lactation was associated with an 880- pound drop in production in the next lactation.

Better cows; more mastitis . . .

So, what have we learned about recurrent mastitis cases and milk production? First, mastitic cows tend to be higher producers than nonmastitic cows before they experience mastitis. Therefore, we should pay particular attention to the higher producers in our herds that are exhibiting clinical signs of mastitis. Focusing on this group of cows, especially if resources (labor, and so forth) are scarce, could save your enterprise a substantial amount of money by catching mastitis cases early and treating them promptly before they cause too much damage or before they even need (antibiotic) treatment. These measures would reduce both absolute milk loss and milk produced but needing to be discarded due to antibiotic presence.

Second, first-calf heifers lost more milk after a second case (436 pounds) than after a first case (361 pounds). The opposite was true for older cows where milk loss was less severe for subsequent cases (557, 524, and 475 pounds for the first, second, and third case, respectively).

Our findings provide information on the differing milk losses associated with mastitis cases, without needing to know the causative agent. Armed with such knowledge, you can better assess the profitability of individual cows. Cows that have repeat mastitis cases may be less desirable to hold on to, as they experience large production drops with every case, taking weeks to recover . . . never returning to their high potential.

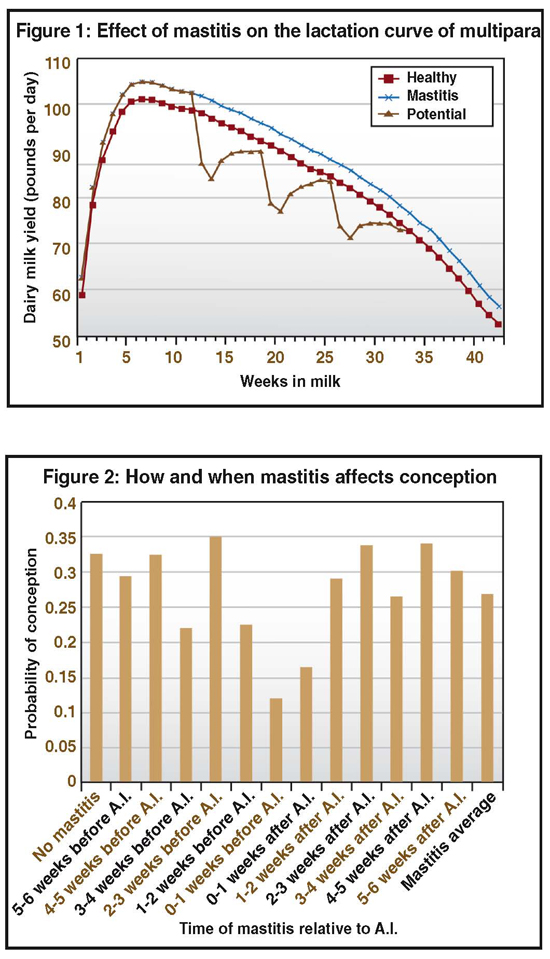

As observed by many dairy producers, we have found that mastitic cows have lower conception rates after artificial insemination (A.I.) and delayed days to first breeding. More recently, we also have found that the timing of mastitis with respect to A.I. can affect the probability of conception.

If mastitis occurred one or two weeks before A.I., probability of conception dropped by 44 percent. If it occurred in the week before A.I., the drop was much greater at 73 percent. If it occurred during the week after an A.I., the decline was 52 percent. So, obviously, mastitis has an impact on reproduction, and it varies with when it occurs (Figure 2). It actually may make sense to refrain from breeding a mastitic cow, and wait for the next cycle, by which time she, hopefully, may have recovered. These are important things to consider when estimating the total cost of a mastitis case.

Shortens life . . .

We also calculated the probabilities of death and sale for a combination of factors (parity, timing of mastitis, stage of lactation, and so forth), based on 16,145 lactations in five New York herds. We found that those probabilities vary with case number and the timing of each case. Mastitis clearly has a detrimental effect on a cow's herd life . . . the probabilities of dying or being sold are much higher for mastitic cows than for nonmastitic cows.

For example, in a second-lactation cow, sale is much more likely after a second case only if it occurs in the first 60 days in milk (approximately 0.05). After this time, it hardly seems to matter if the cow had a second case (0.013 versus 0.011 for a nonmastitic cow). Such results also can be used to economically assess different mastitis management options.

In this article, we have discussed the consequences of mastitis if you only know that your cow had mastitis based on clinical signs. As we have seen, recurrent mastitis cases have different consequences relating to milk yield, conception, death, and sale. We hope that this article has provided some useful information on the varying consequences of mastitis cases.