The author is at the College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, Raleigh.

Recently, I had the opportunity to work with a small Jersey herd that was losing more and more calves. They were developing diarrhea anywhere between 1 and 3 weeks of age and usually dying within 24 hours. The calves seemed fine until they broke with diarrhea, but, despite aggressive treatments, the owner had not been able to save any.

Results from the diagnostic laboratory had indicated only routine causes of diarrhea such as rotavirus and Cryptosporidia. However, neither of these usually is associated with such a sudden death in all calves.

On my first visit to the farm, we looked at the calving area, reviewed the colostrum and calf feeding programs, and evaluated the hutches. Overall cleanliness was good on the farm, and we made only small changes to an already solid colostrum program. The producer decided to thoroughly clean all hutches and then move them to a new area on the farm where there had been no cattle. He also decided to purchase completely new bottles and nipples. Cultures of the milk he was feeding consistently demonstrated extremely low levels of bacterial contamination.

Despite these efforts, the next four calves born on the farm all died by 3 weeks of age. At this point, I began to think something else might be going on. We decided to look for the presence of bovine diarrhea virus (BVD) and submitted ear notch samples from every calf on the farm less than 1 year of age. Out of fewer than 30 calves tested, five came back as positive and were found to be persistently infected with BVD. The farm previously had not had a history of BVD.

We decided to conduct a herd screen in an attempt to determine from where the infection had originated. When we tested every cow in the herd, only one came back as positive. This was an older cow that had been purchased and added to the herd about seven to eight months before the problems started in the calves. Although the cow had been through two lactations and appeared to be perfectly healthy, she indeed was persistently infected with the BVD virus. After a second positive test to verify the first result, the cow was culled. The five calves previously found to be persistently infected also had been removed. After this, calf health slowly began to improve, but we continued to ear notch each calf born.

We decided to conduct a herd screen in an attempt to determine from where the infection had originated. When we tested every cow in the herd, only one came back as positive. This was an older cow that had been purchased and added to the herd about seven to eight months before the problems started in the calves. Although the cow had been through two lactations and appeared to be perfectly healthy, she indeed was persistently infected with the BVD virus. After a second positive test to verify the first result, the cow was culled. The five calves previously found to be persistently infected also had been removed. After this, calf health slowly began to improve, but we continued to ear notch each calf born.

In the five months that passed, all calves born had tested negative for BVD and had been weaned with no health problems. However, in the fifth month after the original herd screen, another newborn was positive for BVD, and follow-up tests confirmed it was a persistently infected animal. The calf's dam tested negative for BVD virus. However, she had been housed in a barn with the old persistently infected adult cow before she was culled from the herd. The farm has not had a positive calf since but continues to test regularly.

Economic losses from BVD can be due to reduced milk production, poor conception rates, and greater calf disease and death loss. The virus spreads primarily by direct contact with secretions (nasal, oral, genital) of cattle infected with the virus. When an animal is first exposed, the virus is spread throughout the body causing only mild disease. Over a 10-day period, the immune system is able to eliminate the infection, and cattle usually are healthy.

The major economic effects of the virus are associated either with suppression of the immune system or disease or death of the fetus, or both. Infection with the BVD virus causes a transient drop in the ability of the immune system to fight off infection which lasts about three weeks. Cattle often develop secondary diseases such as pneumonia.

In the case of the calves described above, infection with BVD virus likely suppressed the already limited immune function of the baby calves. This resulted in death from what normally would be only mild to moderate diarrhea.

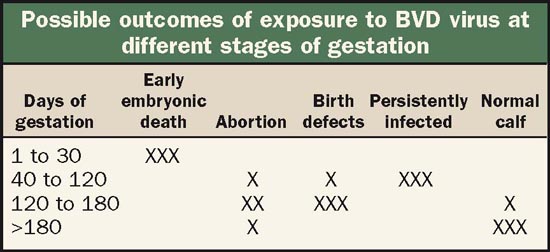

When the calf is exposed to the virus in the early stages of pregnancy, the fetus often is resorbed. This shows up as infertility as cows that are supposed to be pregnant come back in heat. Exposure to the virus between Day 60 to 180 of gestation can result in congenital defects in the fetus, most commonly a condition known as "cerebellar hypoplasia." Calves are very abnormal at birth and don't survive for more than a few days.

Another possible outcome of exposure to the virus in the first three to four months of gestation is persistently infected calves. This happens when the virus is present in the fetus before the immune system of the calf develops. The fetal immune system then considers the virus as a normal part of the calf, and the animal then is never able to mount any type of immune response to BVD. The calves are born infected with the virus and will shed it in their secretions for life, serving as continual sources of infection for other cattle in the herd.

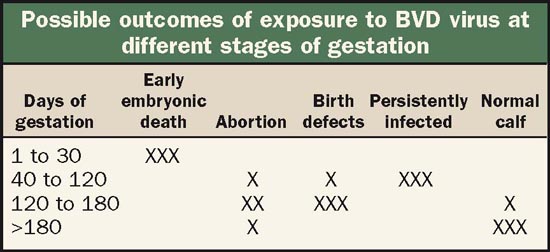

Often, these persistently infected cattle appear normal, and up to 40 percent of them make it into the milking herd. It is not uncommon for them to go undetected in herds for years, and these cows always will produce other persistently infected calves. Exposure of the fetus to the BVD virus late in gestation (after 180 days) typically results in the birth of a normal calf that has antibodies against the BVD virus (see table).

One of the first steps in finding and controlling a BVD problem is to identify and eliminate any persistently infected animals. There are several tests available for this purpose. Some tests use ear notch (skin) samples, some use blood, and one test can even detect the virus in milk.

If you have breeding problems, have had calves born with neurologic signs (such as tremors, seizures, abnormal stance or walk), or, in some cases, if you have unexplained calf losses, talk with your veterinarian about the best way to check for BVD virus. He or she may recommend a complete test of every animal in the herd, or they may recommend "screens" that involve combining blood or milk from a group of animals. Once you are able to eliminate persistently infected animals from the herd, be sure to isolate and test any purchased animals before adding them to the herd.

Discuss vaccination

The other key to controlling BVD virus is establishing an effective vaccination program. I would recommend all dairy herds vaccinate for BVD whether or not they have any persistently infected animals on the farm. Vaccination should be timed so that peak immunity occurs during the early stages of pregnancy as the primary goal is to prevent infection of the fetus.

If you haven't done so already, talk with your veterinarian during the next herd check, and make sure you are using a good BVD vaccine and delivering it at appropriate times.

Click here to return to the Animal Care E-Sources

100125_49

Recently, I had the opportunity to work with a small Jersey herd that was losing more and more calves. They were developing diarrhea anywhere between 1 and 3 weeks of age and usually dying within 24 hours. The calves seemed fine until they broke with diarrhea, but, despite aggressive treatments, the owner had not been able to save any.

Results from the diagnostic laboratory had indicated only routine causes of diarrhea such as rotavirus and Cryptosporidia. However, neither of these usually is associated with such a sudden death in all calves.

On my first visit to the farm, we looked at the calving area, reviewed the colostrum and calf feeding programs, and evaluated the hutches. Overall cleanliness was good on the farm, and we made only small changes to an already solid colostrum program. The producer decided to thoroughly clean all hutches and then move them to a new area on the farm where there had been no cattle. He also decided to purchase completely new bottles and nipples. Cultures of the milk he was feeding consistently demonstrated extremely low levels of bacterial contamination.

Despite these efforts, the next four calves born on the farm all died by 3 weeks of age. At this point, I began to think something else might be going on. We decided to look for the presence of bovine diarrhea virus (BVD) and submitted ear notch samples from every calf on the farm less than 1 year of age. Out of fewer than 30 calves tested, five came back as positive and were found to be persistently infected with BVD. The farm previously had not had a history of BVD.

We decided to conduct a herd screen in an attempt to determine from where the infection had originated. When we tested every cow in the herd, only one came back as positive. This was an older cow that had been purchased and added to the herd about seven to eight months before the problems started in the calves. Although the cow had been through two lactations and appeared to be perfectly healthy, she indeed was persistently infected with the BVD virus. After a second positive test to verify the first result, the cow was culled. The five calves previously found to be persistently infected also had been removed. After this, calf health slowly began to improve, but we continued to ear notch each calf born.

We decided to conduct a herd screen in an attempt to determine from where the infection had originated. When we tested every cow in the herd, only one came back as positive. This was an older cow that had been purchased and added to the herd about seven to eight months before the problems started in the calves. Although the cow had been through two lactations and appeared to be perfectly healthy, she indeed was persistently infected with the BVD virus. After a second positive test to verify the first result, the cow was culled. The five calves previously found to be persistently infected also had been removed. After this, calf health slowly began to improve, but we continued to ear notch each calf born. In the five months that passed, all calves born had tested negative for BVD and had been weaned with no health problems. However, in the fifth month after the original herd screen, another newborn was positive for BVD, and follow-up tests confirmed it was a persistently infected animal. The calf's dam tested negative for BVD virus. However, she had been housed in a barn with the old persistently infected adult cow before she was culled from the herd. The farm has not had a positive calf since but continues to test regularly.

Economic losses from BVD can be due to reduced milk production, poor conception rates, and greater calf disease and death loss. The virus spreads primarily by direct contact with secretions (nasal, oral, genital) of cattle infected with the virus. When an animal is first exposed, the virus is spread throughout the body causing only mild disease. Over a 10-day period, the immune system is able to eliminate the infection, and cattle usually are healthy.

The major economic effects of the virus are associated either with suppression of the immune system or disease or death of the fetus, or both. Infection with the BVD virus causes a transient drop in the ability of the immune system to fight off infection which lasts about three weeks. Cattle often develop secondary diseases such as pneumonia.

In the case of the calves described above, infection with BVD virus likely suppressed the already limited immune function of the baby calves. This resulted in death from what normally would be only mild to moderate diarrhea.

When the calf is exposed to the virus in the early stages of pregnancy, the fetus often is resorbed. This shows up as infertility as cows that are supposed to be pregnant come back in heat. Exposure to the virus between Day 60 to 180 of gestation can result in congenital defects in the fetus, most commonly a condition known as "cerebellar hypoplasia." Calves are very abnormal at birth and don't survive for more than a few days.

Another possible outcome of exposure to the virus in the first three to four months of gestation is persistently infected calves. This happens when the virus is present in the fetus before the immune system of the calf develops. The fetal immune system then considers the virus as a normal part of the calf, and the animal then is never able to mount any type of immune response to BVD. The calves are born infected with the virus and will shed it in their secretions for life, serving as continual sources of infection for other cattle in the herd.

Often, these persistently infected cattle appear normal, and up to 40 percent of them make it into the milking herd. It is not uncommon for them to go undetected in herds for years, and these cows always will produce other persistently infected calves. Exposure of the fetus to the BVD virus late in gestation (after 180 days) typically results in the birth of a normal calf that has antibodies against the BVD virus (see table).

One of the first steps in finding and controlling a BVD problem is to identify and eliminate any persistently infected animals. There are several tests available for this purpose. Some tests use ear notch (skin) samples, some use blood, and one test can even detect the virus in milk.

If you have breeding problems, have had calves born with neurologic signs (such as tremors, seizures, abnormal stance or walk), or, in some cases, if you have unexplained calf losses, talk with your veterinarian about the best way to check for BVD virus. He or she may recommend a complete test of every animal in the herd, or they may recommend "screens" that involve combining blood or milk from a group of animals. Once you are able to eliminate persistently infected animals from the herd, be sure to isolate and test any purchased animals before adding them to the herd.

Discuss vaccination

The other key to controlling BVD virus is establishing an effective vaccination program. I would recommend all dairy herds vaccinate for BVD whether or not they have any persistently infected animals on the farm. Vaccination should be timed so that peak immunity occurs during the early stages of pregnancy as the primary goal is to prevent infection of the fetus.

If you haven't done so already, talk with your veterinarian during the next herd check, and make sure you are using a good BVD vaccine and delivering it at appropriate times.

100125_49