The author is at the College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, Raleigh.

I've received numerous questions recently from local dairy producers who have heard about proposed changes to the use of antibiotics in livestock that are to be phased in over the next few years. They are primarily wondering what the new rules are and how it will affect them.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has implemented a voluntary plan in partnership with the pharmaceutical industry to phase out the use of certain antibiotics for improved growth rates or enhanced feed efficiency in food animal agriculture. They have also implemented a plan to phase out certain "over-the-counter" drugs and make sure all antibiotics will have to be prescribed for use by a veterinarian.

The new guidelines

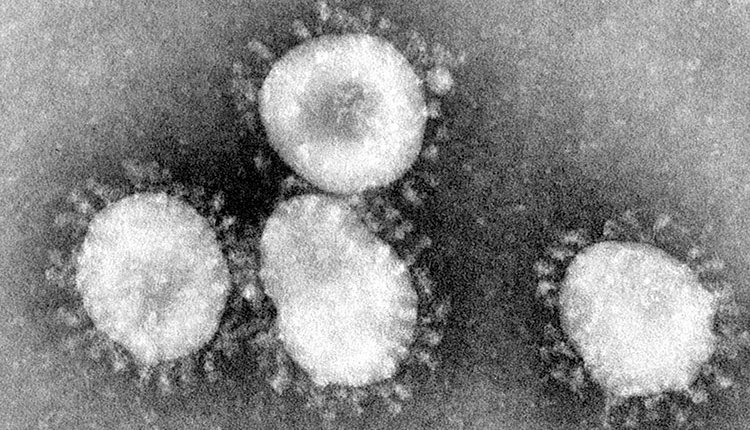

In late 2013, the FDA released two major Guidances or "rules bulletins," if you will. In Guidance 209, they talk about how important antibiotics are to the treatment of human diseases. They also state that resistance to antibiotics is on the rise and that use of antibiotics in both humans and animals can lead to resistance. Therefore, they consider the use of "medically important" antibiotics in food animals a major concern, particularly when used for production purposes to enhance growth or improve feed efficiency.

In this Guidance document, the FDA asks all pharmaceutical companies that sell antibiotics for use in livestock to voluntarily remove all references to "growth enhancement" or "improved feed efficiency" from their labels within the next three years. The FDA is making the process voluntary because it is the fastest way for them to accomplish this goal.

If they were to wait for Congress to pass laws prohibiting the feeding of antibiotics to livestock to improve weight gain, it could take many years. As it stands, most major pharmaceutical companies have already announced their intent to voluntarily comply with this ruling.

The other major change being proposed by the FDA under Guidance 213 is to limit feed and water antibiotics in food animals to "uses that include veterinary oversight or consultation." Currently, there are several older feed grade antibiotics that are considered "over-the-counter" or don't specifically require a prescription to purchase or use. Under the new rules, all antibiotics that are fed to cattle would require a special prescription.

This prescription is called a veterinary feed directive or VFD. The VFD rules were originally passed in 1996 to cover medicated feeds. Since 1996, every "new" antibiotic that has been approved for use in feed has had to go through a VFD process to be used legally on farms. The VFD places a much greater emphasis on professional (veterinary) control while still allowing cattle producers to obtain medicated feeds efficiently and cost-effectively. Currently, the only antibiotic that falls under the VFD category for cattle is Tilmicosin (Pulmotil) which is approved for control of respiratory disease in beef cattle.

Work with your vet

The initial requirement of using a VFD-medicated feed is a valid veterinarian-client-patient relationship, which very broadly means you will need to have a relationship with a veterinarian to get feed-grade antibiotics. Once a veterinarian has made an initial diagnosis, they can issue a signed VFD on a preprinted, multipart form. The veterinarian gives the form to the producer, who then orders the medicated feed. A VFD feed may not be distributed to a producer without a signed VFD form.

Now the FDA is asking pharmaceutical companies to voluntarily withdraw all feed-grade antibiotics that have an over-the-counter label and transition them to a veterinary feed directive form, so acquiring these products will require the help of a veterinarian.

How will this change affect dairy producers? Fortunately, for most dairymen it should cause minimal, if any, change. The new rules are aimed only at antibiotics administered orally or in feed. Since there are currently no antibiotics approved for improving growth rate or feed efficiency in dairy cattle, the first change (removing growth promotion labels for feed-grade antibiotics) should have no effect on dairy operations. Likely, the biggest effect will be on feedlot cattle.

The second change - requiring veterinary oversight to obtain feed-grade antibiotics - could have some implication for dairy farms. For example, if you currently purchase antibiotics to add to milk replacer for the treatment of calf diarrhea, you will eventually have to get this through a veterinarian. These rules may be extended to oral antibiotics so that they are no longer available without a veterinary prescription.

The FDA feels that making producers work through a veterinarian will lower the amount of what they consider "unnecessary" antibiotic use. Again, these changes are expected to be phased in over the next three years. At this point in time, these new laws will not apply to any injectable antibiotics. Products like penicillin or LA-200 will still be available for purchase over the counter. These new rules only apply to drugs that are administered orally or in feed.

Just the beginning

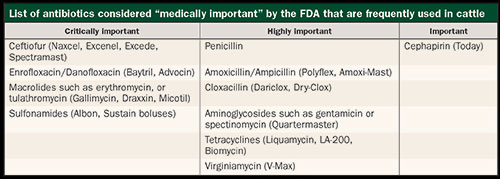

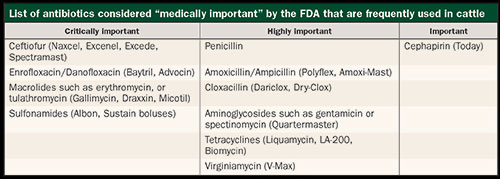

The one specific product excluded from this list are ionophores (Rumensin, Bovatec). Although these are also technically considered antibiotics, they are not deemed medically important to humans and, therefore, aren't covered in the new Guidances. However, virtually every other antibiotic we use is considered medically important to humans (see table), and the FDA is going to try and curtail their use in livestock species. I don't expect these new rules to be the end of changes moving forward that are designed to limit the amount of antibiotics used in production animals.

But, for the time being, the drug laws at this point should cause minimal changes to the dairy industry. If you aren't working with a veterinarian regularly, you will probably want to look into changing that in the next year or two. If you already have a good veterinary-client-patient relationship, then you should be able to conduct business as usual.

Click here to return to the Animal Care E-Sources

1406_395

I've received numerous questions recently from local dairy producers who have heard about proposed changes to the use of antibiotics in livestock that are to be phased in over the next few years. They are primarily wondering what the new rules are and how it will affect them.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has implemented a voluntary plan in partnership with the pharmaceutical industry to phase out the use of certain antibiotics for improved growth rates or enhanced feed efficiency in food animal agriculture. They have also implemented a plan to phase out certain "over-the-counter" drugs and make sure all antibiotics will have to be prescribed for use by a veterinarian.

The new guidelines

In late 2013, the FDA released two major Guidances or "rules bulletins," if you will. In Guidance 209, they talk about how important antibiotics are to the treatment of human diseases. They also state that resistance to antibiotics is on the rise and that use of antibiotics in both humans and animals can lead to resistance. Therefore, they consider the use of "medically important" antibiotics in food animals a major concern, particularly when used for production purposes to enhance growth or improve feed efficiency.

In this Guidance document, the FDA asks all pharmaceutical companies that sell antibiotics for use in livestock to voluntarily remove all references to "growth enhancement" or "improved feed efficiency" from their labels within the next three years. The FDA is making the process voluntary because it is the fastest way for them to accomplish this goal.

If they were to wait for Congress to pass laws prohibiting the feeding of antibiotics to livestock to improve weight gain, it could take many years. As it stands, most major pharmaceutical companies have already announced their intent to voluntarily comply with this ruling.

The other major change being proposed by the FDA under Guidance 213 is to limit feed and water antibiotics in food animals to "uses that include veterinary oversight or consultation." Currently, there are several older feed grade antibiotics that are considered "over-the-counter" or don't specifically require a prescription to purchase or use. Under the new rules, all antibiotics that are fed to cattle would require a special prescription.

This prescription is called a veterinary feed directive or VFD. The VFD rules were originally passed in 1996 to cover medicated feeds. Since 1996, every "new" antibiotic that has been approved for use in feed has had to go through a VFD process to be used legally on farms. The VFD places a much greater emphasis on professional (veterinary) control while still allowing cattle producers to obtain medicated feeds efficiently and cost-effectively. Currently, the only antibiotic that falls under the VFD category for cattle is Tilmicosin (Pulmotil) which is approved for control of respiratory disease in beef cattle.

Work with your vet

The initial requirement of using a VFD-medicated feed is a valid veterinarian-client-patient relationship, which very broadly means you will need to have a relationship with a veterinarian to get feed-grade antibiotics. Once a veterinarian has made an initial diagnosis, they can issue a signed VFD on a preprinted, multipart form. The veterinarian gives the form to the producer, who then orders the medicated feed. A VFD feed may not be distributed to a producer without a signed VFD form.

Now the FDA is asking pharmaceutical companies to voluntarily withdraw all feed-grade antibiotics that have an over-the-counter label and transition them to a veterinary feed directive form, so acquiring these products will require the help of a veterinarian.

How will this change affect dairy producers? Fortunately, for most dairymen it should cause minimal, if any, change. The new rules are aimed only at antibiotics administered orally or in feed. Since there are currently no antibiotics approved for improving growth rate or feed efficiency in dairy cattle, the first change (removing growth promotion labels for feed-grade antibiotics) should have no effect on dairy operations. Likely, the biggest effect will be on feedlot cattle.

The second change - requiring veterinary oversight to obtain feed-grade antibiotics - could have some implication for dairy farms. For example, if you currently purchase antibiotics to add to milk replacer for the treatment of calf diarrhea, you will eventually have to get this through a veterinarian. These rules may be extended to oral antibiotics so that they are no longer available without a veterinary prescription.

The FDA feels that making producers work through a veterinarian will lower the amount of what they consider "unnecessary" antibiotic use. Again, these changes are expected to be phased in over the next three years. At this point in time, these new laws will not apply to any injectable antibiotics. Products like penicillin or LA-200 will still be available for purchase over the counter. These new rules only apply to drugs that are administered orally or in feed.

Just the beginning

The one specific product excluded from this list are ionophores (Rumensin, Bovatec). Although these are also technically considered antibiotics, they are not deemed medically important to humans and, therefore, aren't covered in the new Guidances. However, virtually every other antibiotic we use is considered medically important to humans (see table), and the FDA is going to try and curtail their use in livestock species. I don't expect these new rules to be the end of changes moving forward that are designed to limit the amount of antibiotics used in production animals.

But, for the time being, the drug laws at this point should cause minimal changes to the dairy industry. If you aren't working with a veterinarian regularly, you will probably want to look into changing that in the next year or two. If you already have a good veterinary-client-patient relationship, then you should be able to conduct business as usual.

1406_395